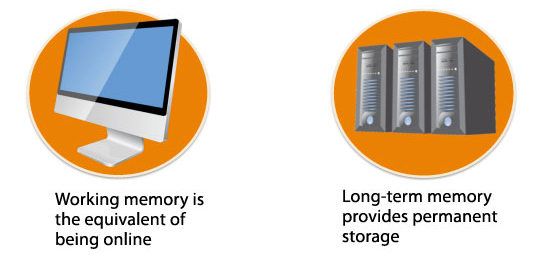

Working memory (WM) is the aspect of our brain that manipulates information in the moment. It affects most everything we do in terms of learning. This creates a challenge, because working memory can only process around three to four bits of information at one time. As if that’s not enough, information in working memory lasts only around ten seconds. These conditions set up the phenomenon known as cognitive load. But let’s start at the beginning.

Working Memory: Small Capacity and Short Duration

The fact that our working memories have a small capacity and a short duration is what we are up against as people who want to learn and as learning experience designers.

Interactions Between Working Memory and Long-Term Memory

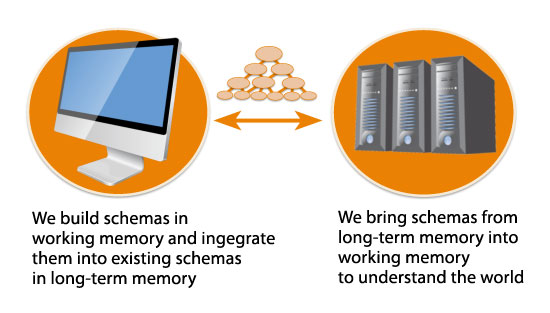

Unlike working memory, long-term memory appears to have an unlimited capacity. Information in long-term memory (LTM) is stored in schemas, which are mental structures we use to organize and structure knowledge. Schemas incorporate multiple elements of information into a single element with a specific function.

The interaction goes both ways. We construct new schemas in working memory so they can be integrated into existing knowledge in long-term memory. And existing knowledge in LTM is brought into working memory to help us understand the world. Otherwise, everything would be new all the time!

Working Memory is Vulnerable to Overload

As you have most likely experienced, sometimes learning involves great effort. That’s because working memory is quite vulnerable to overload. This occurs as we study increasingly complex subjects and perform increasingly complex tasks. As learning experience designers, we have to be aware of cognitive load, which refers to the total amount of mental activity imposed on working memory in any one instant.

What causes too much demand on working memory? One cause comes from an abundance of novel information. More information than a person can process. But high cognitive load is also strongly influenced by the number of elements in working memory that interact with each other. Often, complex learning is based on interacting elements that must be processed simultaneously. For example, learning to drive involves understanding how several elements simultaneously interact, such as considering the pressure required to brake, the amount to turn the steering wheel, staying alert to traffic conditions and making adjustments for weather conditions.

Intrinsic and Extraneous Cognitive Load

Not all cognitive load is bad. But a problem arises when the load exceeds the capacity of the person processing it. Cognitive Load Theory discusses two types of cognitive load: intrinsic and extraneous (or some call it extrinsic).

- Intrinsic Load. This type of cognitive load refers to the complexity of what you are learning. Consider the amount of new information and how it all interacts. Intrinsic cognitive load is an essential part of the learning task over which we don’t have control.

- Extraneous Load. If a learning experience is unnecessarily difficult or confusing, it results in extraneous cognitive load. That is, it uses up cognitive resources that learners could direct at the learning task. It is a result of poor learning design that can have a negative effect on learning. Extraneous load can interfere with the construction or automation of schemas.

What We Can Do

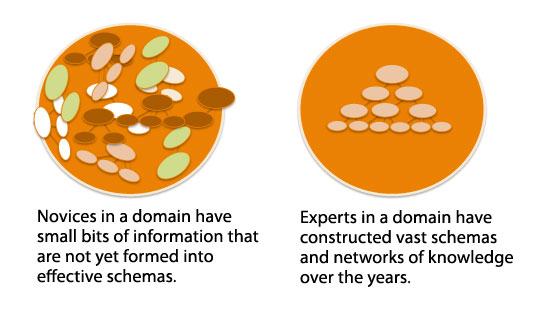

Two things that instructional designers can focus on to free working memory capacity are helping learners construct schemas and helping them automate schemas. Effective instructional design can help people combine elements of lower level schemas into higher-level schemas. This is one indicator of expertise. When a person is able to chunk multiple elements of information together, there is more working memory capacity available for solving problems and processing information.

In addition, one can automate schemas through repeatedly applying them. When we automate schemas, we no longer process them in working memory. Thus, they free working memory capacity for other activities. Some types of schemas that become automated are reading and driving a car.

As learners becomes increasingly familiar with content and skills, schemas change so that the information or task can be handled more efficiently by working memory. Our job is to facilitate this change in schemas, which ultimately, is what learning is all about. Listen to this interview with John Sweller, the developer of Cognitive Load Theory.

You may also want to read:

- 20 Facts About Working Memory

- Long-term Memory: A User’s Guide

- Novice Versus Expert Design Strategies

- The Novice Brain

Very insightful and well explained that the process of learning is storing short term memory into schema. I assume that creating exercises that prompt recall, explanation, application, etc. help the student to develop the schema, but also I wonder how we might be able to think of organizing the schema into types of heuristics and algorithms for higher order functioning such as problem solving and creating? And the bigger question is: how should the instructional designer or teacher use this “how people learn” concept when creating educational experiences?

What happens when you fill out the form to get the book? It should send it to you in an email. Please let me know if that’s not working.

Best,

Connie

Hello Connie,

Thanks for the inspiring article. Can you tell me how to get your fee e-book?

Regards,

LIL

Welcome, Nuha. CL is a fascinating theory. More on this topic is coming. In the meantime, check this out: Six Strategies You May Not Be Using to Reduce Cognitive Load.

Thanks Connie. From my several decades of learning and teaching you just made me understand the basic culprits for not easily comprehending what I learn as well as my inability to easily impart knowledge to my students. You have got a new fan.

Thanks for the kind words, Arun.I’m glad this clarified things for you.

Connie

Hi Connie

“Working Memory and cognitive load “. The best presentation I have ever seen in this topic . Some magic in your style to make the readers understand the concepts perfectly. Great Respect

Hi Nazanin,

The date is: Mar 28, 2011.

Connie

I really liked your article, and I want to cite some parts of it in my own article. Can I have the exact details about the day it was posted or the conference and the exact title of the subject you presented?

Thank you

Hi Kodjo,

I’m glad it helped. It makes sense to me this way too. I know it’s somewhat theoretical and over time the model will change. There is criticism that the environment and body are left out of this information processing model (see embodied cognition). I look forward to seeing how the theory evolves! Thanks for your comment.

Connie

Reading the article brought to the fore for me, how learning occurs.

Linking Working Memory to Long Term Memory as Online and Permanent Storage respectively clearly helped me to understand the process of learning, starting from simple to complex excercises

This is not my original work. I’m not a researcher. Information about cognitive load is pretty much in the public domain so I don’t think there’s a need to list all the people who have researched it. I’m happy you did though! Thank you.

Yes, you’ll have to read those other articles linked below for strategies. I like to focus on one thing at a time and go deep. But really, you may not find many strategies for teachers. The site is geared for instructional designers, though I’m thrilled when educators/teachers read the articles too and welcome their input. Thanks for your comment.

I am sorry if I missed where you gave credit for the research on CL. Did you give credit where credit is due? (John Sweller, Paul Ayres, Slava Kalyuga, and others). Or were you trying to pass this article off as you original work?

Also, you make no mention of anything practical a teacher can do to implement strategies that manage CL. This comes in later articles and is germane to the proper application of the theory.

Hi Brad,

It’s nice to have your comments on the site. I understand you were fulfilling an assignment and it’s no problem. I’m sorry for teasing you (it’s a bad habit). I look forward to interacting with you here. I wish you well in your schooling.

Best,

Connie

Connie,

Thanks for allowing me to comment to your blog for this weeks assignment. I hope to be a frequent commenter on your blog and I promise that I will be less formal less formal and use a more conversational tone.

Regards,

Brad

Hi Brad,

I can’t say I’ve had entire college essays with references in these comments, but I hope you do well in this course.

Best,

Connie

Instructional designers need to take into account the working memory when developing content for the learner. The first step in the ADDIE process is to complete an assessment. According to Dick, Carey, and Carey, a learner analysis must be completed to determine the target population’s prior knowledge and behaviors as well as their motivation and abilities (Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2005). This is the same concept that is used by presenters; they want to know their audience. Because the working memory can only handle a small amount of information, between 5 and 9 items, at any time and the length of time to hold this information is short, it is important that strategies are in place to allow the information to move from the working memory to the long-term memory as efficiently as possible. One of these strategies is referred to as chunking or associating the information into larger chunks the learner can relate to (Ormrod, Schunk, & Gredler, 2009). By chunking the information it will allow the learner to associate the information to existing schemas moving the information into the long-term memory more efficiently and making recall easier.

To build upon and increase existing schemas or created new schemas the instructional designer should use the information acquired in the assessment phase to determine the prior knowledge and behaviors and design instruction that is slightly above the learner’s cognition or skill level (Cole, John-Steiner, Scribner, & Souberman, 1978). Using Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, the learner will be able to expand on an existing schema, strengthening it, instead of attempting to create a new and immature schema. For example, children learn addition and subtraction before they learn multiplication and division. It is easier to teach a child that 5×5=25 when you can show them that 5×5= 5+5+5+5+5= 25. If they do not know addition it will be difficult understand the concept of multiplication. The design of any education or instruction should be planned to deliver a meaningful learning experience by taking into account the way individuals process information they receive through all of there senses.

Thank you for a great article,

Brad

References:

Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., & Souberman, E. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, J. (2005). The systematic design of instruction (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson

Ormrod, J., Schunk, D., & Gredler, M. (2009). Learning theories and instruction (Laureate custom edition). New York: Pearson.

Hi Connie, I used your website for an assignment where I identified useful instructional design websites. This week for our class we are looking at neuroscience and information processing. One of the major topics on our discussion board is people not being able to retain content and having to reread material several times in order to be able to retrieve it. One of the suggestions from our text was to use meta cognition. I think that at times even with years of experience a lot of us are not experts in the field of instructional design. This causes us to experience overload when reading our text as sometimes we have nothing to reference and as you noted above I think this falls into the intrinsic cognitive load category.

Hi Munira,

Thanks for sharing your approach for dealing with working memory through mind mapping. Please feel free to share your ideas in this Mind Mapping article too!

Connie

Hi Connie

I really appreciate the simplicity in which you have shown such complicated information. As instructional designers this information is very important and relevant to the way we design our instruction. Many times the information on our courses maybe very new to the students, and our role is to find a way of connecting this information to preexisting schemata or find ways to organize this information so that students can understand it.

For this I really like to use mind mapping as this not only helps students to link the different parts of the information, but also helps with the organization of it. The mind map also mimics the way our brain organizes information and supports the schema theory.

Mind mapping also helps with WM overload and helps students to later recall this information as the mind map really helps visual learners. I also find that when I am going to introduce a new topic, getting students to mind map on what they already know helps to put them at ease and reduces some of the anxiety related to learning new material. This then helps them to tap into any existing schemata and use that as a support structure for the new information.

Hi Dennis,

I appreciate your comment, even though my name is Connie. Hope my articles are helpful to you.

Best,

Connie

Hi Jane – this is a helpful explanation of cognitive overload. I’ll be bookmarking this, thanks for sharing. Dennis

Wow. Great article. I haven’t thought that much about how the memory effects learning since my first year of university over 10 years ago. Thanks for the stimulating read.

Very, very comprehensible. U rock.

Thanks, Jane. And I guess I hadn’t thought of that! This article is building schemas too. It’s infinite.

I am laughing as I write this comment. I started to thank you for your excellent article and the way it presented such a clear model of the thousands of little things that have to happen as we move from novice to expert – and realized your entire article was a schema of its own – a clear capsule that I can use today as I work. Thanks, Connie, for another excellent viewpoint.