During a presentation I gave several years ago, an audience member commented that he teaches older adults how to use software programs. “When these adult students don’t understand a concept, they are more likely to comprehend it if the concept is explained by a peer,” he said.

Someone wondered if this was because peers are more likely to have similar knowledge structures compared to the knowledge structures of the instructor. I think this is a logical explanation.

The implication here is that we could design more effective learning experiences if we approached a subject as though we were the peers of the target audience. Not only does this mean we would need an empathetic perspective, but that we would actually try to understand the knowledge structures of these learners.

Schemas are Knowledge Structures

Theoretical knowledge structures, known as schematas or schemas in cognitive psychology, refer to the way we organize and store knowledge in long-term memory. A schema is thought to be a network of information that represents concepts, situations, events, and actions in memory. Schemas incorporate all of this into a single framework, acting as a mental shortcut to help us quickly understand, interpret and react to the world.

Cognitive psychologists theorize that we rely on schemas to reconstruct memories of events. When a concept is presented, schemas get activated and in turn, activate associated schemas. Because the schemas are not perfect replications, our reconstructed memories are not perfect either.

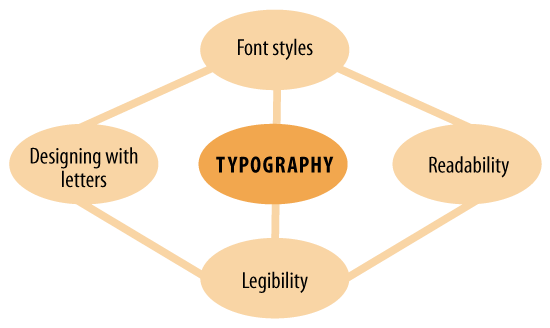

A simple example of a schema for the category “typography” might include these concepts: designing with letters, font styles, readability, legibility. Although your schemas change as you learn and gain experience, when someone mentions typography, you have a general idea of what they mean and perhaps a positive or negative memory of trying to design slide titles.

The Curse of Knowledge

A Schema for Typography

When people are acquiring information or a new skill, their knowledge structures are more limited, less organized and have fewer connections than those of an expert. The schemas of an expert, according to theory, are richer, more complex and well-connected. This is why experts are generally competent problem solvers.

The downside? Experts find it difficult to remember what it’s like to be a novice—a deadly condition we all know of as The Curse of Knowledge. When you know a lot about something, when your skills are advanced, it becomes hard to imagine not knowing it. That’s why experts are not always the best teachers.

You can overcome this predicament by understanding the schemas of your learners. It’s a critical skill for those who design learning experiences because learners can only understand something based on what they already know. Learning is analogical. That’s why a basic rule is to help learners recall prior knowledge.

Understanding Prior Knowledge

As a network of knowledge, schemas influence the way new information is integrated. Therefore, when new information is not connected to a schema, it is difficult to recall. And information that is inconsistent with a person’s schemas is also difficult to recall. Imagine it just floating around somewhere in the mind. That’s why it’s important to have a sense of a learner’s current knowledge network, so that you can design for it.

In the fascinating book, The Art of Changing the Brain, author James E. Zull develops several ideas about prior knowledge (though he discusses this in terms of neuronal networks):

- Prior knowledge is based on each person’s life experiences.

- Prior knowledge is persistent. People don’t change their schemas simply because an expert or instructor says something else is true. An existing schema can hinder learning new information.

- Prior knowledge is always the beginning of new knowledge; new knowledge builds on existing knowledge.

- In order to communicate with someone, you need to find a common language based on prior knowledge.

Human-centered Design

In human-centered design approaches, such as Design Thinking and Game Thinking, designers are encouraged to use empathetic techniques to better understand audience members and users. Through conversations, interviews and observations, we can attempt to discover how people think and organize certain concepts. The goal is to find out what learners already know and how they perceive the world by asking them and discussing their answers. If you can discover what is in the brains of your learners during analysis and design, you may be less likely to go back and revise because training wasn’t effective. Still, discussions that occur after learning can also provide insight for future courses.

What are some ways to “read the minds” of a target population?

- Observe them performing related tasks at work

- Chat with them informally

- Interview them

- Give them a relevant survey with open-ended questions

- Provide opportunities for virtual chats before and after they’ve taken a course

- Encourage user-generated content

- Try the flipped learning approach where learners view content ahead of time. Then synchronous events consist of conversation and dialog.

James Zull, the author referred to above, notes that in small classes, he asks students to explain their previous experience and also asks them specific questions that show their ideas of a concept. As a science professor, these questions might be something like, “Write what your idea of a gene is.” or “Draw your idea.” In this way, he peers into the brains of his students and designs learning experiences starting where their knowledge exists. Certainly we can learn from and incorporate this approach in the workplace.

I love when you know an approach is correct and smile , even before you learned about the brain science behind it. Re, “Learning is analogical… where I taught the Windows OS and apps to adult learners said I was the “Queen of Analogies.” An example: to teach about switching among applications, I would place a deck of cards (Solitaire), and I love your kindness to empower the people across the world. you are really my hero.

A strong audience analysis informs designers about learners’ motivation, learning preferences and challenges as well as their background knowledge in the subject area. This analysis will help the designer tailor instruction to novices versus expert learners, high school graduates versus college graduates, and new employees versus long-term employees. Instruction is not a one-size-fits all construct; therefore, a thorough audience analysis ensures that training meets the needs of all learners!

You’re awesome! You’ve got the perfect mind for designing learning experiences.

Connie

I love when you know an approach is correct, even before you learned about the brain science behind it. Re, “Learning is analogical…” Many years ago, the program director where I taught the Windows OS and apps to adult learners said I was the “Queen of Analogies.” An example: to teach about switching among applications, I would place a deck of cards (Solitaire), a little notepad (Notepad or Wordpad), a small hand calculator (Calc) and a paintbox (Paint) on the real desktop. I would switch among these, bringing them into the “foreground” as the Learners clicked on buttons on the taskbar, or used Alt+tab to switch among applications on their virtual desktops.

Great tips and insights, Matthew. Thanks for taking the time to share them.

Connie

How much time I have with the student helps me determine how to approach the course.

I teach clinical software to newly hired employees at a major health system. The other part of my job is creating eLearning modules that either zero in on software simulation or offer education to the entire health system population.

Regardless of what I teach or what I produce, I start by defining what I want the user to take away from the learning. With that information I break it down into the simplest form possible and start piecing it back together.

Being able to provide a story along the way helps the learner to retain the information.

I like to build in checkpoints in each situation to check learning progress and allow the learners to test their knowledge.